“Art is art. Fashion is fashion.” — Karl Lagerfeld [1]

…

…

House of CHANEL Suit

House of CHANEL (French, founded 1910), Karl Lagerfeld (French, born Germany, 1933–2019). Suit, autumn/winter 2008–9. Jacket and skirt of polyurethane; shirt of cotton poplin. Courtesy CHANEL.

…

Created for the autumn/winter 2008–09 ready-to-wear season and made of black and clear polyurethane, this Chanel suit design assimilates dress and other artistic references. The ensemble’s angular silhouette is borrowed from eighteenth-century imperial Chinese armor. Lagerfeld often looked beyond the canon of fashion history for design inspiration and frequently consulted auction catalogues and museum collections as reference material. Within the archived sources that detail the production of the collection is a photocopy of a rare foot-soldier’s uniform, scanned from a catalogue of the 1995 exhibition Heaven’s Embroidered Cloths: One Thousand Years of Chinese Textiles at the Hong Kong Museum.

Manchu military ceremonial uniform, 1766. Silk satin, gilt metal, lacquer, and horsehair: 75cm, skirt length: 80cm. Hong Kong Museum of Art

…

Dated to 1776, during the reign of the Qianlong emperor (1736–95), this uniform, made for ceremonial processions rather than for battle, consists mainly of a cream-colored silk satin jacket and matching apron skirt, both edged in navy blue silk satin and studded with gilt metal rivets in the brigandine-style of dingjia (“armor with nails”).[2] The trapezoidal shape of the jacket and skirt are echoed in the silhouette of the Chanel suit. However, the metal studs that decorate the exterior of the armor—originally there to hold protective internal metal plates in place—have been replaced by abstracted Matisse-like botanical and geometric motifs. These cover the ensemble’s entire surface, recalling the foliate appliqués of Hungarian-American designer and textile artist Mariska Karasz.

Mariska Karasz (American, Budapest, 1898–1960). Ensemble ca. 1927. Silk. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Katherine J. Judson, in memory of Jeanne Wertheimer, 1977 (1977.284.2a, b)

…

This example of Karasz’s work, made around 1927, was acquired by The Costume Institute in 1977. Composed of a matching coat and dress, this day ensemble of navy silk faille is decorated with hemmed appliqués of cream-colored silk crepe and is ostensibly the source of inspiration for the motifs that appear on the surface of the Chanel suit. It was included in the 1998–99 exhibition Cubism and Fashion, where curator Richard Martin paired it in the catalogue with Picasso’s painting Queen Isabella (1908). The purpose of the juxtaposition was to exemplify the inter-planar dynamism of “float[ing] fragments and pieces above and below one another on an ambiguous plane,” describing not only the technical praxis of collage and of Cubism but also the embellished surface of Karasz’s creation.[3] The complexity of floating forms against an ambiguous background is pushed to its fullest potential in Lagerfeld’s design. Instead of Karasz’s solid blue ground, Lagerfeld uses a transparent colorless polyurethane—upon which Karasz’s motifs appear as if suspended in air—effectively eliminating the visible boundary of the garment’s surface and simultaneously revealing yet another plane underneath.

…

House of CHANEL Dress

House of CHANEL (French, founded 1910), Karl Lagerfeld (French, born Germany, 1933–2019). Dress, spring/summer 1984 haute couture. Silk organza, glass beads and crystals. Courtesy CHANEL.

…

This entirely beaded Chanel evening gown was created during the beginning of Lagerfeld’s thirty-seven-year tenure at Chanel for the spring/summer couture season of 1984—then only the designer’s third couture collection for the house. It is an especially fine and masterful example of couture hand embroidery executed by the House of Lesage in collaboration with Chanel. In an article from Women’s Wear Daily from January 1984, Lagerfeld described the blue-and-white porcelain-inspired motifs as being “right out of a portrait by Sargent.”[4]

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882. Oil on canvas, 87 3/8 x 87 5/8 in. (221.93 x 222.57 cm). Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit. Courtesy MFA Boston

…

Perhaps Lagerfeld was referring to The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (1882), the celebrated group portrait made famous by its quiet introspection and unusual composition in which two large blue-and-white nineteenth-century Japanese porcelain vases dwarf the painting’s four youthful subjects. Despite this evocation, the Chanel evening gown borrows its decorative motifs from blue-and-white eighteenth-century imperial Chinese porcelain. (An extant example of this Jingdezhen ware design is housed at The Met.) The pattern, which teems with sprays of ripe fruit and peony, chrysanthemum, and lotus blossoms, is rendered in blue cobalt-based underglaze that is hand-painted over white porcelain.

Hexagonal vase with Rococo-style flowers, 18th century. Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong periiod (1736–95), China. Porcelain painted in underglaze cobalt blue (Jingdezhen ware), H. 27 1/4 in. (69.2 cm); Diam. 12 1/4 in. (31.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Paul E. Manheim, 1966 (66.156.1)

…

The gown, which Hebe Dorsey described in the International Herald Tribune as one of the “best moments”[5] of the collection, consists of a ground of white silk organza with the painted motifs of the ceramic diligently reconstituted across the gown’s surface with thousands of embroidered blue, white, and clear seed beads and crystals. The total amount of time to achieve this was a remarkable 1,800 hours of handwork.

…

Chloé “Astoria” Dress

CHLOÉ (French, founded 1952), Karl Lagerfeld (French, born Germany, 1933–2019). “Astoria” dress, spring/summer 1967. Silk crepe de chine. Courtesy CHLOÉ.

…

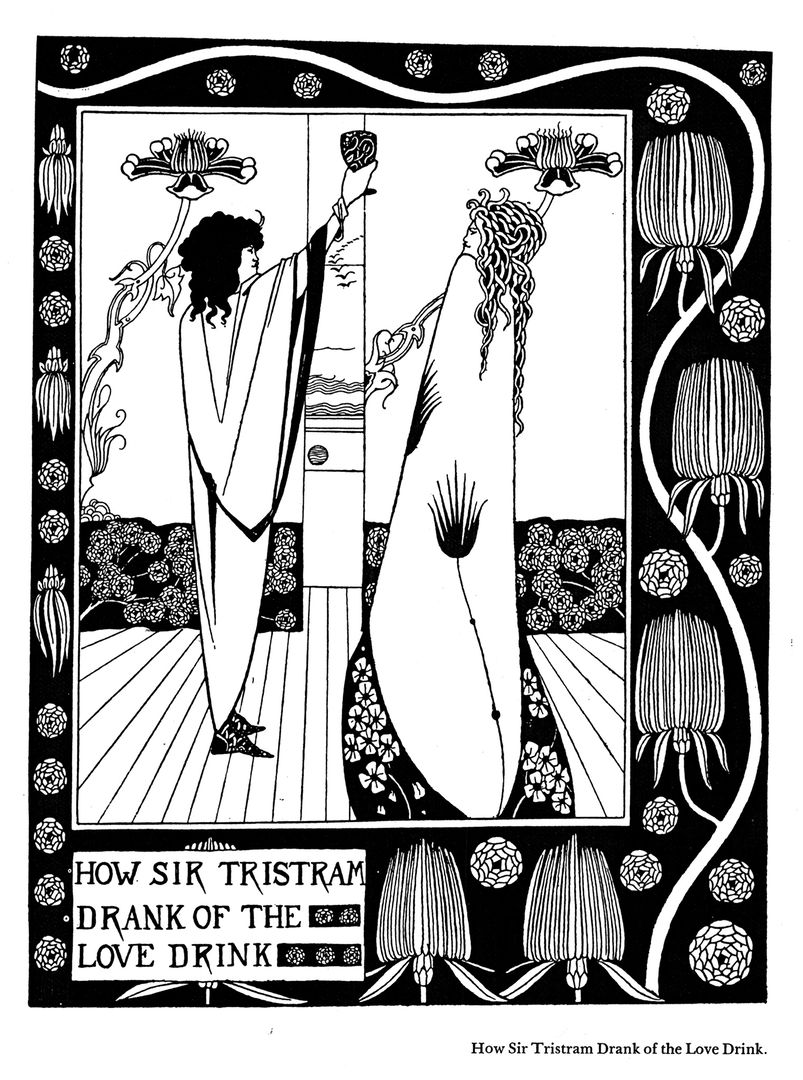

This Chloé dress belongs to the spring/summer 1967 collection, created during the early years of Lagerfeld’s twenty-four year on-and-off creative partnership with Chloé that began in 1964 and ended in 1997. The design of the dress, which is made of ivory silk crepe de chine, is inspired by the prolific British illustrator Aubrey Beardsley’s sensuous interpretation of Sir Thomas Malory’s fifteenth-century Arthurian classic Le Morte d’Arthur. For Lagerfeld, who, as a young boy, dreamed of becoming a professional illustrator and caricaturist, Beardsley’s work presented a seemingly endless well of inspiration. Over the course of his life, he dedicatedly collected the artist’s work for his own personal collection. Once, in 2017, he even paid a bookdealer friend to fly to New York for the sole purpose of bidding on and winning three small Beardsley vignettes at auction.[6]

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley (British, 1872 – 1898). How Sir Tristram Drank of the Love Drink, 1893. Ink and graphite on wove paper, 28.3 x 22.1 cm.

…

In particular, the “Astoria” dress borrows its motifs from an illustration that depicts the chivalric romance of Tristram and Isolde, titled How Sir Tristram Drank of the Love Drink. The illustration appeared in the 1893 edition of Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, published by J. M. Dent & Co. The detailed border of Beardsley’s illustration, with its bold stylized floral imagery and continuous serpentine line, can be seen in Lagerfeld’s design, mainly down the center front of the dress. Additionally, the cape of the figure on the right (Isolde) serves as a reference in both its composition of large-bulbed flowers set against a white ground, with sinuous stems sprouting from the hem. The four-petaled cruciform flowers that decorate the sloping bottom border of Isolde’s cape also appear in the same place of the “Astoria” dress in a similar configuration.

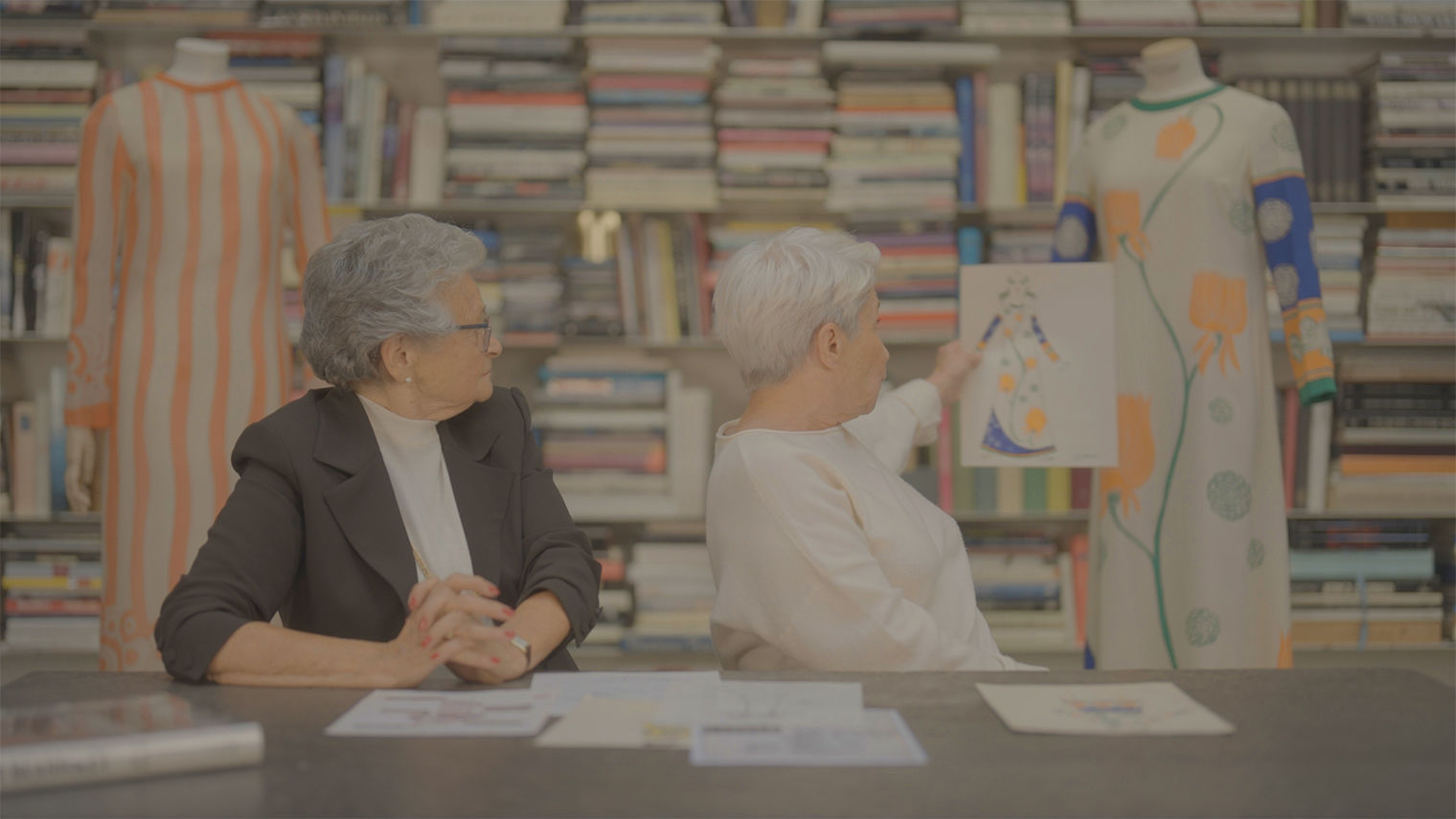

Still from an interview with Anita Briey, former première d’atelier at Karl Lagerfeld, and Nicole Lefort, former textile artist for Chloé, 2022. Courtesy Deralf/Bangumi

…

The colorful surface of the dress is achieved through a technique of silk-painting called serti, in which a design is outlined on stretched fabric with a resist (to keep the paint from bleeding), then filled in with paint, and finally set with heat. While at Chloé, Lagerfeld designed many dresses that utilized the serti technique, each one carried out, by hand, by textile artist and collaborator Nicole Lefort, who began at Chloé just two years after him in the fall of 1966. This level of hand-based, artisanal craftsmanship is usually reserved for couture rather than for ready-to-wear garments; Lefort’s artistry elevated Chloé’s ready-to-wear designs like the “Astoria” dress to remarkable levels. Of all of the hand-painted dresses she created with Lagerfeld, Lefort shared in an interview, the “Astoria” dress was quite popular, with somewhere between 100 and 150 produced.[7] She proudly added that “[t]hey all came out of my workshop—that’s important to me—and there were no prints. [Each dress] was hand painted.”[8]

…

There are many more artistic references within Lagerfeld’s body of work that are well-documented within the exhibition and its catalogue. While most of the objects within the show are presented with the sketches that preceded them, many ensembles are also paired with images of the artworks that inspired them.

…

…

SWOW SWAG

__________________________________________________________________________________