Marxists Do It Better

The 1972 exhibition was not a unified movement built around a political or aesthetic manifesto, though its participants did share a mutual allergy toward the blooming consumption society of post-war Italy. For Radical Design, the most revolting outcome of this conversion to consumerism was the increase in material separation between the Italian workers and the upper middle class during the mid ’60s and early ’70s. Portrayed in the cinema of Vittorio de Sica and Ettore Scola, the shantytowns that spread across the outskirts of Milan or Rome were in sharp contrast to the domestic aspirations portrayed in Italian design magazines. Thus, the artists’ attitude toward design and architecture oscillated from suspicion to total rejection—design could no longer be separated from day-to-day politics.

Contrary to the Modernist belief that utopia resulted from the omniscient vision of a demiurge architect, the Radical Design group thought that it had to be invented from within the domestic nucleus by its very members. The ideological responsibility of the avant-garde to invent new futures had been transferred from urban planning and architecture to the field of design. In that process, the model of the nuclear family imposed by the development of capitalism during the 19th century had to be completely rethought. Italy: the New Domestic Landscape was an attack against the bourgeois dwelling, which was vertically structured around the figure of the paterfamilias (the head of a Roman household). Any avant- garde movement or counterculture needs an enemy to exist, both real and imaginary. For Radical Design—as for many avant-garde movements from the ‘60s, such as the French Situationist, the British Independent Group, and the trans-European COBRA Movement—this figure was embodied by the mythical father of Modernism, Le Corbusier. A surgeon of rationalism, the Swiss-French designer thought of the urban space as a continuous assembly line of functions that had to be mastered by the architect himself.

Infused with ’60s Situationist thinking, the Radical Design group wanted to counter the alienating power of post-war domestic liturgy conceptualized in 1920 by Le Corbusier as a “machine for living.” Following the economic boom of the ‘50s, the motto “design dictates, users follow” was the matrix of mass consumption society. The picture of the perfect nuclear family was aggressively projected into every household through magazines, radio, and television. The vision of two children playing innocently in front of the loving eye of their mother while their father was reading a newspaper became the canonical embodiment of happiness and social accomplishment. For the movements emerging in the ‘60s, domestic life impoverished individual creativity and spirituality by luring people into composing a tastefully designed home.

Against the idea of the heroic designer enforcing predetermined solutions, the artists defended a conception of design as an ecosystem that stressed the notion of play within everyday life. This is how in 1972—almost four decades after MoMA’s first design exhibition Machine Art curated by Philip Johnson in 1934—the museum introduced Marxist design discourse to New York City.

For an Archipelago of Utopias

In its time, Italy: the New Domestic Landscape was divided in two categories: 180 objects produced over its current decade, and 11 environments commissioned by the museum for the exhibition. The curator’s overall objective was to portray the way the Italian avant-garde responded to the task of creating newly-designed spaces for the future.

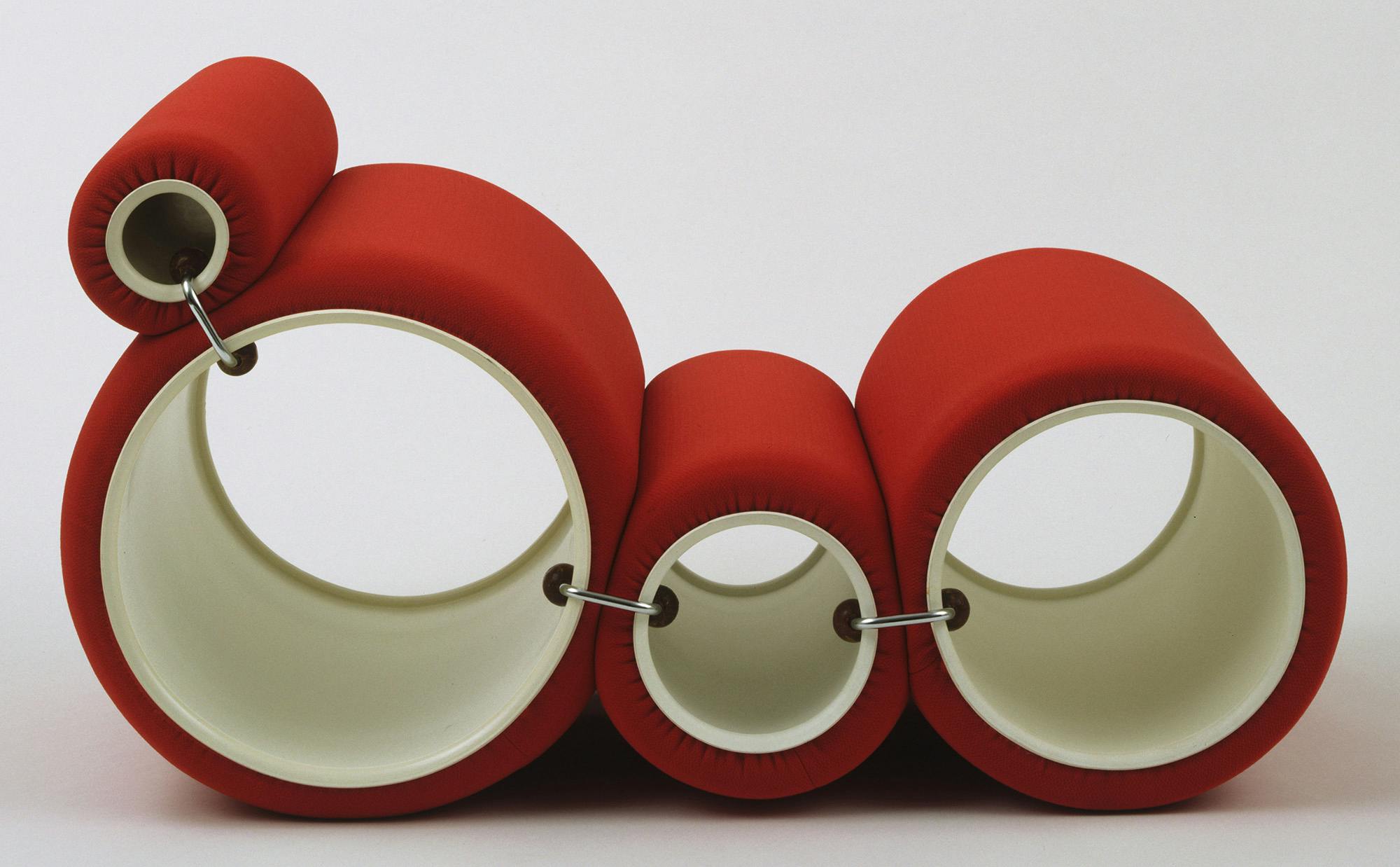

The first section was divided into three subcategories: conformist, reformist, and contestatory. This organization was meant to represent a political gradation from the hopeful pro-design section to the staunchly anti-design. Yet, the distinction was hardly noticeable to the viewer, because all the objects were installed within pine and plexiglas crates that mimicked the dizzying effect of Milan’s shopping mall Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II. In addition, Ambasz’s contestatory discourse was not expressed via the refusal to produce objects, but was affiliated with modular or formless design. Among the most notorious examples were the “Sacco Bean Bag Chair” designed by Piero Gatti, Cesare Paolini, and Franco Teodoro in 1968, Joe Colombo’s “Tube Chair of Nesting and Combinable Elements” from 1969, and Bruno Munari’s “Abitacolo” (“Cockpit”) habitable structure from 1971. Yet, despite this apparent innocence, it was the dissemination of creativity within all aspects of life—the constant fight against intellectual boredom and routine— that were driving these designers. “Imagine trying to be stuffy while slouching in a bean bag chair,” Ambasz wrote in the exhibition ctalogue. The household was to become the laboratory for new types of interactions between people and objects, between objects themselves, and, ultimately, between people. After the economic recovery from World War II, boredom became enemy number one for Europe’s avant-gardes. Play was to be injected at every stage of existence. This vision stemmed from a conception of the object not as a finished formal entity, but as a social cluster bomb capable of fragmenting from within the traditional family system. The modular sofa was an ideological Trojan Horse meant to reform the micropolitics of every household and induce its transition from a space of authoritarian enforcement to a space of democratic consensus.

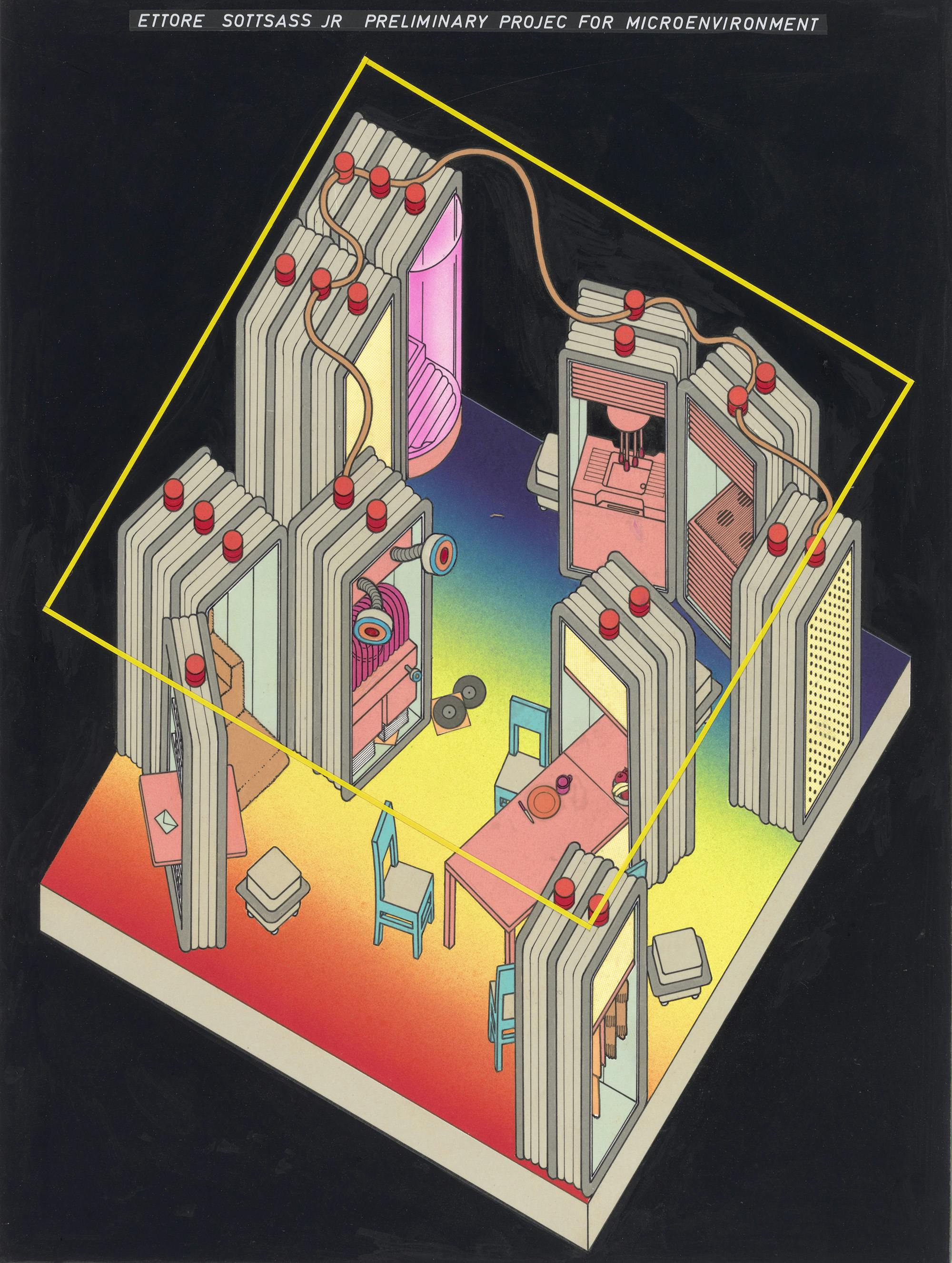

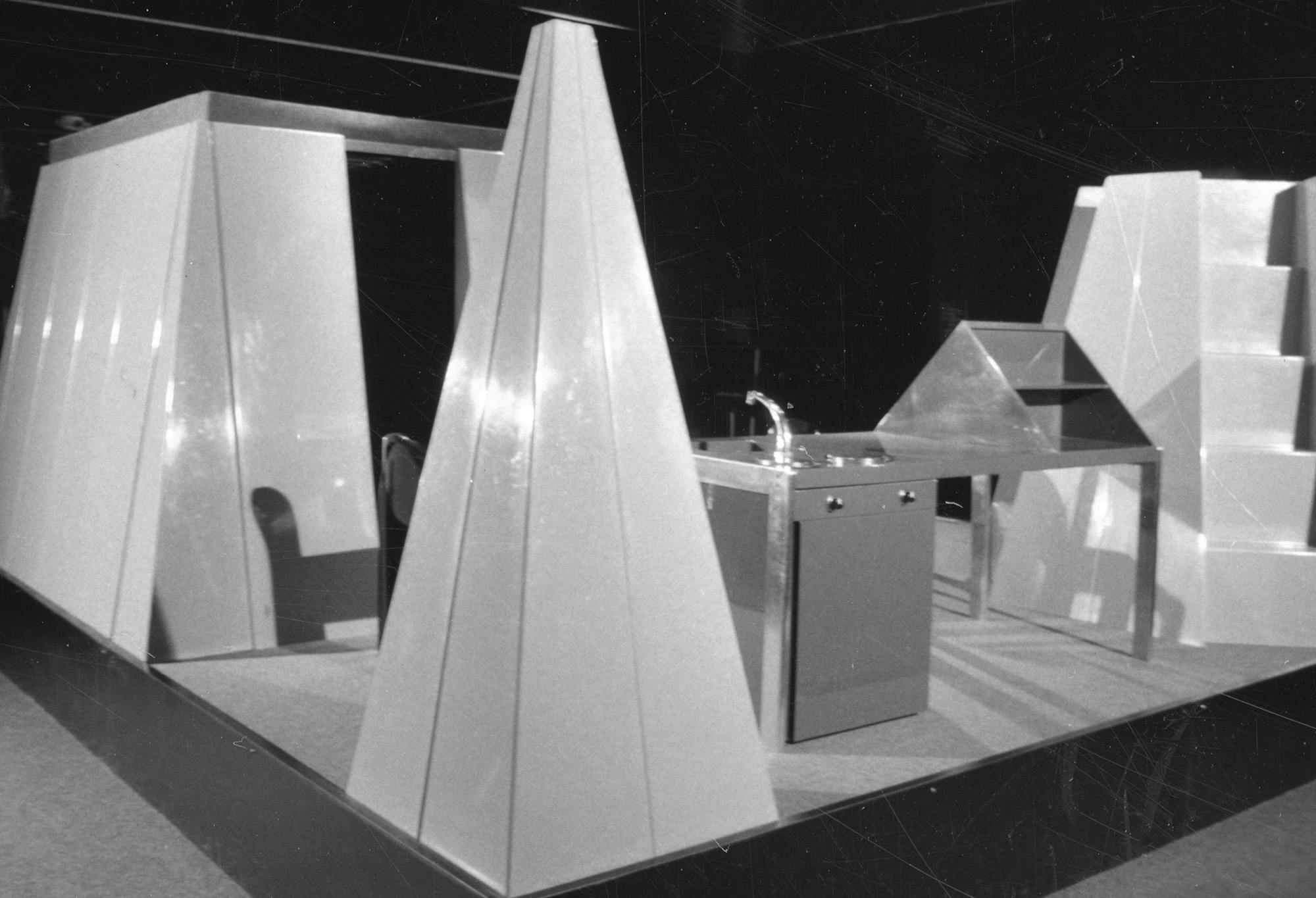

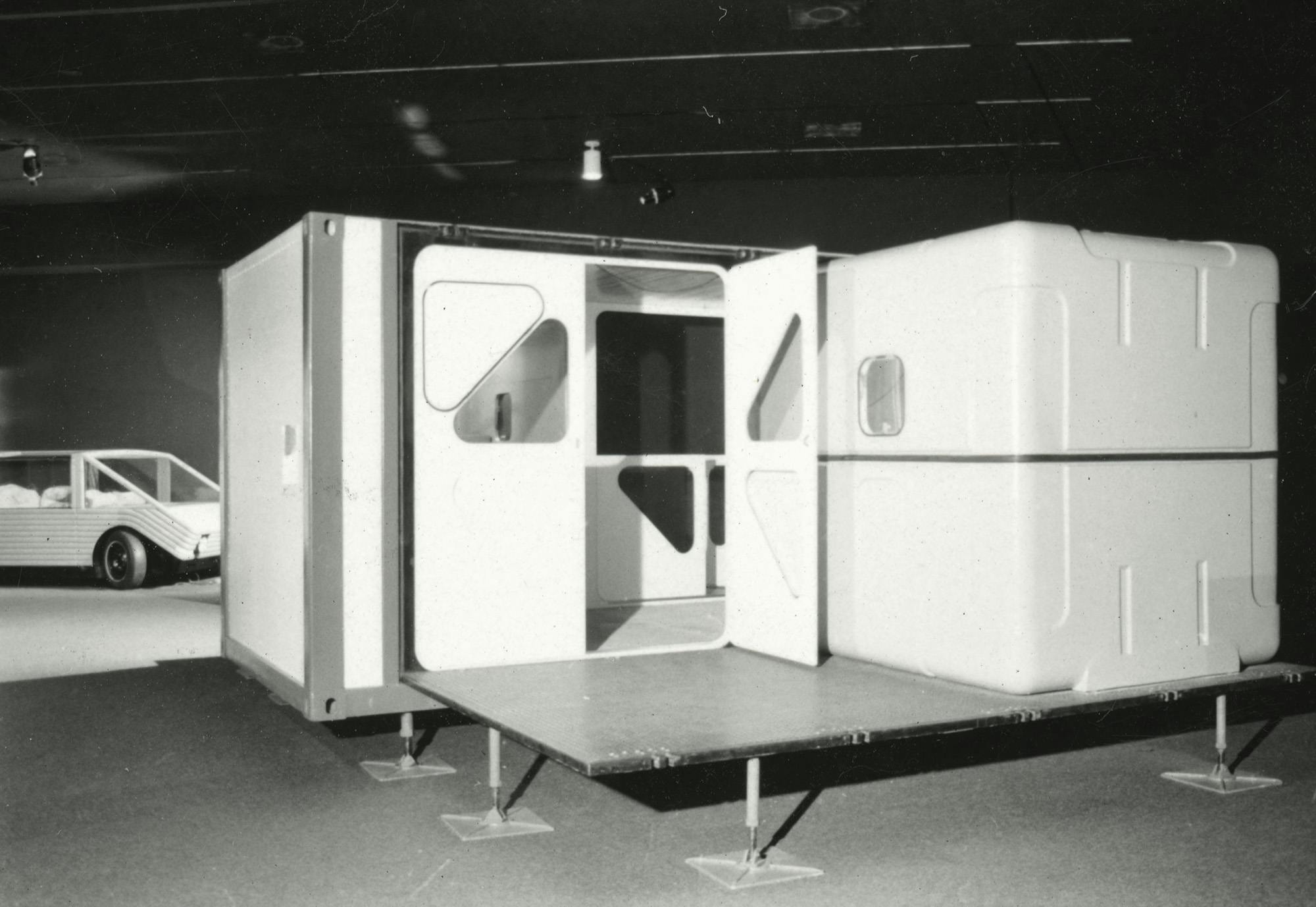

Yet, it was the environment section of Italy: the New Domestic Landscape that gathered the most radical stance toward design. Divided once again into two categories—pro- and anti-design—the former believed in the capacity of design to transform social relationships, especially within the family circle, while the latter was convinced that society was already saturated with objects and that political change was the priority. Among the pro-design pieces, three were based on a modular environment: Ettore Sottsass’ serial system of domestic units on wheels, Gae Aulenti’s red architectonic elements that could be rearranged, and Joe Colombo’s yellow compact “Total Furnishing Unit.” The other four environments were mobile units, the most original being Mario Bellini’s green “Kar-a-sutra,” which, as its name suggests, was an arrangeable orgy bed installed in a familial car. On the other hand, the anti-design group focused on installations inspired by cybernetics theory. Ugo La Pietra designed a triangular domestic cell that was to operate as a communicational node within the larger global media realm. It was a criticism against thetransformationofthehomebythetelevisionintoapassive media receptor. Superstudio created a small cubic installation elevated from the floor and composed of a one-way polarized mirror with its floor gridded in order to symbolize a continuous infrastructure of communication systems. Inside, the space was infinitely reflected. A small television was installed within the cube presenting the film Supersurface: An Alternative Model for Life on the Earth that depicted families living in this new type of continuous media structure. Archizoom presented an empty room with a voice musing on the necessity of an archipelago of utopias, each fitted for one’s own sake. These last two environments represented the most radical discourse on utopian thinking, as they proposed negative utopias that were not ambitioning at building ideal cities. Instead, they aimed at eradicating architecture and city planning altogether in order to let every household build their own.

The Family is Dead; Long Live Families!

In her article “Six Steps To Abolish The Family,” queer thinker M. E. O’Brien proposed rethinking parenthood, love, and intimacy outside of the bourgeois understanding of the nuclear family. She notably went through the liberationist movements of the 1970s and homosexual revolutionaries such as Mario Mieli in Italy, Guy Hocquenghem in France, and David Fernbach in Great Britain. In its most radical participations, Italy: the New Domestic Landscape echoed this call against the family as a reactionary political entity. Some artists in the show claimed a total withdrawal from the design field, arguing that every object prior to any ideological upheaval served as a reactionary system. As Adolfo Natalini from Superstudio stated in 1971, “If design is merely an inducement to consume, then we must reject design; if architecture is merely the codifying of bourgeois model of ownership and society, then we must reject architecture…Until then, design must disappear. We can live without architecture.” The family as the first model of socialization was at the forefront of this fight. The understanding of the household was transitioning from being considered a space of sedimentation of power relationships to a space of micropolitical experiments that would birth alternative ways of living, being together, and loving each other. Ultimately, new forms of subjectivities would arise free of all the formal and social rules attached to the patriarchal system.

Five decades following the exhibition, what has been the legacy of the Radical Design group? Well, it would be easy to dismiss it on the grounds that their behavioral design and reflection on the media environment has nurtured the Silicon Valley techno-liberalist ethos. The presence of the beanbag chair in every startup’s office has now almost become the totem of their superficial slogans of disruption. Yet, the artists’ understanding of utopia as a set of micropolitical rituals instead of the reification of one’s ideology might be their most lasting imprint on today’s queer politics. As the interspecies friendship between the child and fox in The Little Prince revealed in the middle of the Second World War, domesticity can also be a revolutionary practice.

…